New calculations issued alongside the Spring Budget show just how higher rate taxpaying status is becoming ever more common.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) received plenty of attention leading up to the Budget. It was widely portrayed in the media as the body that placed constraints on the Chancellor’s tax-cutting options ahead of the coming election.

That portrayal of the OBR’s powers is an over-simplification. While the OBR does calculate whether the Chancellor can meet his fiscal rules, it neither sets those rules nor, crucially, the assumptions underlying the calculations. For example, in projecting how much tax revenue the government will receive from 2025/26 onwards, the OBR is obliged to follow the Treasury’s assumption that the ‘temporary’ 5p cut in fuel duty will be scrapped and duty itself will rise in line with the Retail Price Index (RPI) inflation. Nobody, least of all the OBR, believes this will happen. Fuel duty rates last rose in 2010.

Despite these limitations, or perhaps because of them, the OBR has paid increasing attention to the impact of planned tax changes (or lack thereof), highlighting facts that the Chancellor might prefer not to discuss.

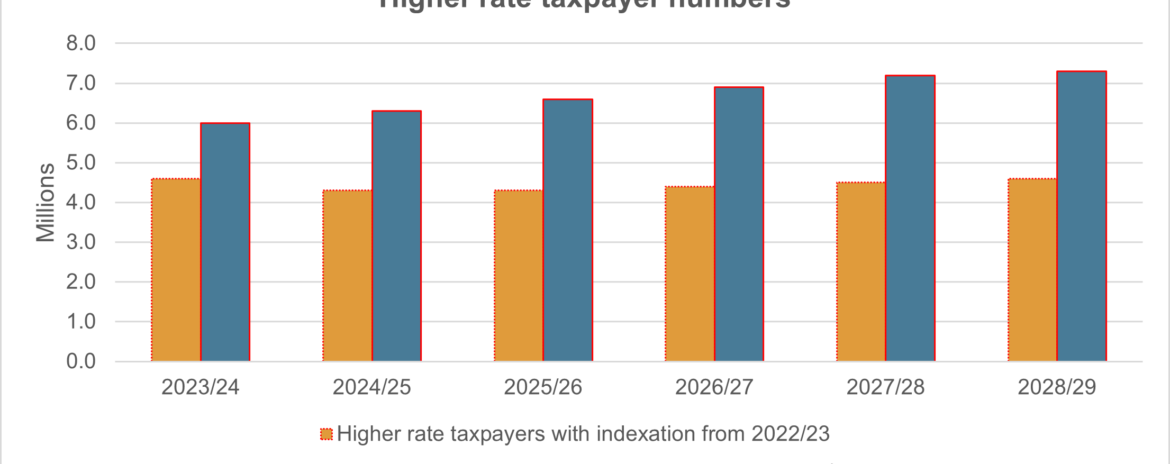

A good example, which the OBR has regularly highlighted in its reports, is the consequences of freezing the personal allowance and higher rate income tax threshold until April 2028. The impact of this freeze on the population of higher rate taxpayers is demonstrated in the graph below. By 2028/29, the OBR estimates that there will be 7.3 million falling into this category, 2.7 million (59%) more than if indexation had applied to the higher rate threshold.

That is not the entire story – the near-£25,000 cut to the additional rate threshold in 2023, followed by an indeterminate freeze, will result in 0.6 million more additional rate taxpayers. Overall, the OBR estimates that about two in nine income taxpayers will be paying more than the basic rate by 2028/29.

Source: OBR EFO March 2024